From Scientist to Marketer: The Data-Driven Journey of Nick Copping

Never a dull moment with Nick, here with Jeremy Gunn, Stanford men's soccer head coach at our 2016 ZOOM Client Dinner

Our Co-CEO Nick Copping started his career in upper atmospheric physics at NASA. How did he transition from collecting data in space to a career in technology and ultimately marketing? Follow his journey and fascination with data.

How did you get into science?

When I was little, I was always fascinated about the way things moved. Why did wheels follow a certain path, why did cars go certain ways, and why when you threw a ball did it arc? That was the observable stuff. But I was also interested in the way electricity behaved and how sound worked it’s magic.

At age 8, I found a few old books in the library and started studying electricity, vacuum tubes and transistor circuits. I built my first vacuum tube amplifier. The trouble is vacuum tubes use 500-600 volts, in what's called a plate voltage. So it was a little dangerous for an eight-year-old to start fiddling around this stuff, but I’m here today to tell the story. My father wasn't so happy with my vacuum tube experiments; he was a mechanical engineer who couldn’t help me much with electrical engineering and was quite concerned when he read 500 volts on my meter.

“It was a natural curiosity of how and why things work by exploring data.”

I didn’t know what they were called at the time, but at the age of ten I discovered differential equations, and that I could write my own. That’s when I really started experimenting with data, adjusting and learning the “why” of how things worked. If I put a certain voltage in a circuit, what was the response? By using a meter, I could sort out what the tubes were doing by analyzing the data. If I pushed on something, in a certain spot with a certain force, where did it go? If I could listen to something and I could change the frequency and harmonic content, what was going on?

So that’s how I got into science. It was a natural curiosity of how and why things work by exploring data.

Where did your curiosity take you next?

I went on to the physics program at Caltech, studying under Nobel Peace Prize winner Richard Feynman. After I graduated, I was working on UARS—upper atmospheric research satellite—at NASA where we were trying to sort out ozone depletion in the atmosphere due to chemical refrigerants like Freon. Since the ozone energy signatures were at such a high frequency, it took complicated wave guides and instrumentation to capture the data, so once again, here I was chasing data to understand chemical interactions in the sky. Since this raw ozone data needed to be analyzed, it was sent to a HP computer, which didn’t talk well to the HP operating software. I eventually got someone to help me write a piece of complicated machine code to analyze the data, which was my entry into the world of software. I went from NASA to Hewlett Packard as a systems engineer, at Feynman’s suggestion given my curiosity with technology.

At HP, my first assignment was to attend a 13-week training. I managed four interminable weeks, then cut class so I could talk directly to the engineers who make HP products. Chuck House, the Head of R&D, referred to me as a renegade like himself, bucking the system to accomplish what I was hired to do: find out what technical customers need and make sure they get it. Chuck and I knew that in order for HP to survive, it must put customers’ needs first. We were turning HP’s engineering-driven culture on its head to a customer-driven focus.

That’s when I began considering the power of data to help solve customer problems.

We started leveraging systems engineers to collect regionalized data from customers about how well products fit a business or technical need. Not only that, but how do you describe those needs? What's the value of that product in terms of their business and our technology? This data didn’t exist for the computing division (the hardware side), it existed in the consumer world for toothpaste and soap. For example, when we brought Unix into HP, we needed to figure out what people were trying to do with Unix in both technical and business environments. We put together the HP Unix Users Group as a way to get that information. I was the chairman of that group for years as I advanced to the R&D Manager at HP Software Labs.

How did you go from technologist to marketer?

I left HP and started working with Kleiner Perkins companies. I discovered an interesting pattern. Every time I asked anyone other than an engineer how to explain something, the answers weren’t very good. Even founders who were really sharp technical people couldn’t explain what they were doing.

There were plenty of inventions, but no invention around how to explain both the market need and how the product filled that need, i.e.,marketing. I found myself trying to do positioning and explain stuff, but again, I needed data.

Meanwhile, I started running a company that developed one of the first object-oriented databases. We sold that technology to the French government, then used the product to build the digital documentation system for the Boeing 777 aircraft. I came back to Silicon Valley and joined ParcPlace-Digitalk during the battle over Smalltalk and Java technology.

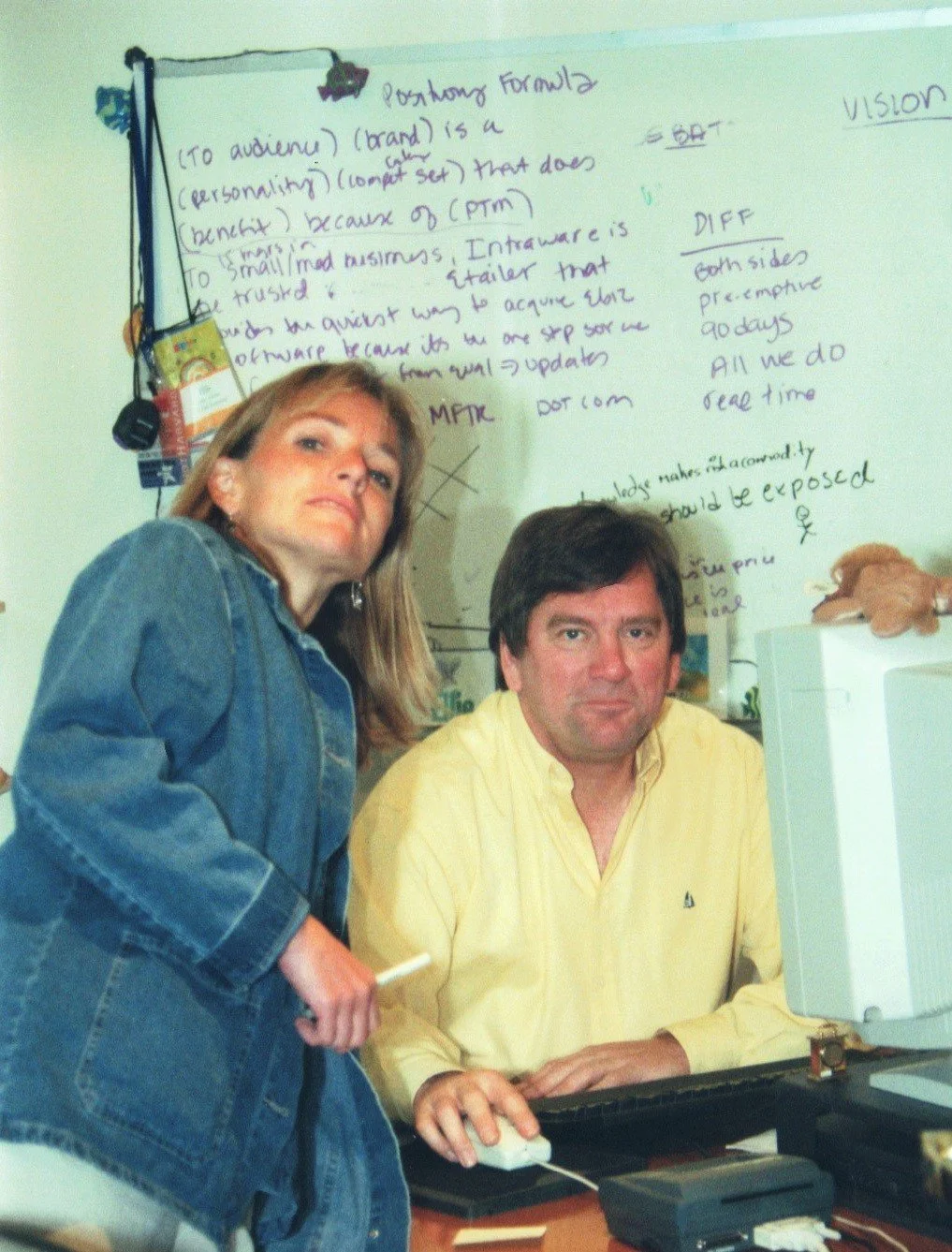

Nick & Ellie during the early days of ZOOM Marketing

It was about that time I met Ellie Victor at Cunningham Communication, where she led PR for their software and services clients. Her challenge was that every time we sat down to do work on the message, again people couldn't explain what they did and what made it different. Sound familiar?

We spent about a year going back and forth about trying to figure out what to do about that which generated the inspiration underpinning soon to be ZOOM. We started with the scientific method, and crafted the data-driven process to get to what’s different, and learn how to explain it in the frame of a market need with data from actual customers and prospects. We then started ZOOM Marketing. One of our first clients was Adobe and we’ve used our data-driven process to successfully position hundreds of companies over the past 26 years. We’ve been lucky to work with some of the most innovative companies, helping them figure out how to explain their uniqueness in a customer-focused way and helped our clients generate a quarter of a trillion dollars in market value.

What are the similarities between technology and marketing?

Standing back and thinking about it, both technology and marketing are driven by innovation and data.

In technology, R&D folks are always figuring out new solutions and ways to advance what they're doing in the field. And in marketing, people are constantly looking for new ways to reach, engage and sell to customers. So the idea of innovation exists in both camps. They do different things, but both fields innovate.

“Both technology and marketing are driven by innovation and data.”

When it comes to using data in marketing, it’s much more advanced today than it was in my early career. Now marketing relies heavily on data to make decisions based on consumer behavior and trends, and it measures the effectiveness of the efforts. In technology, data is still used to design, improve and optimize products. Both are much more customer centric.

As we’ve seen over the years, there’s way more collaboration between marketing and technology. That’s the magic. We tell our clients that positioning success is when sales is selling what engineering is building and marketing is marketing. That’s part of the beauty of a data-driven positioning process. You get everyone on the same page climbing the same hill.